Bostonians of the Year are selected by the editors of the Globe Magazine. Send comments to magazine@globe.com

_____

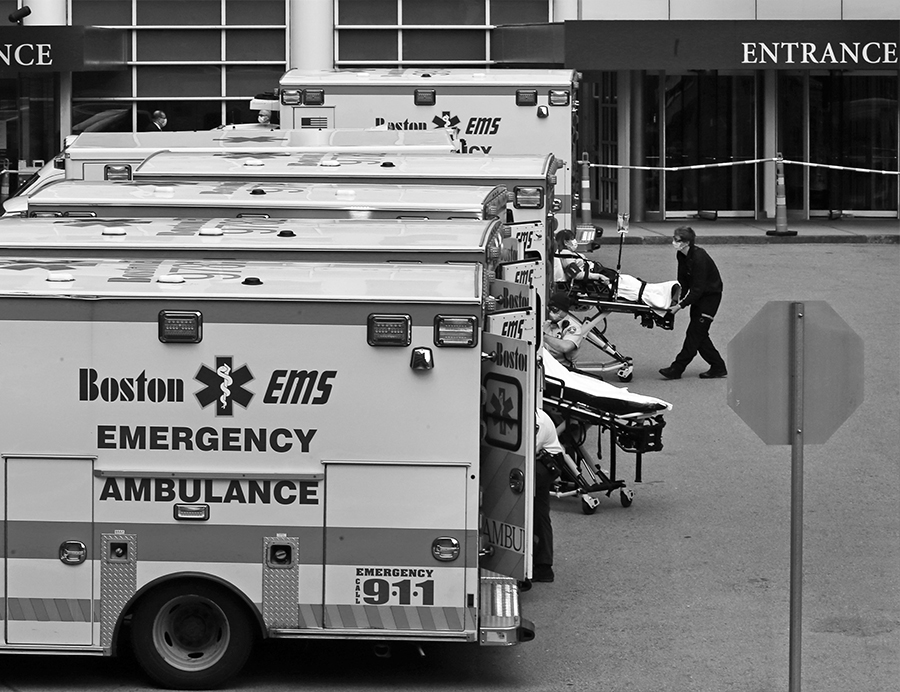

When the coronavirus crisis engulfed Massachusetts in March, shuttering businesses and sending people scurrying behind closed doors, it quickly became clear that many workers would have to continue reporting to their jobs to keep society from collapsing: Doctors. Nurses. Health care support staff. Farmers. Seafood processors. Grocery store workers. Police officers. Firefighters. Teachers. Child-care providers. Pharmacy clerks. Bus drivers. Flight attendants. Package deliverers. Bank employees. Homeless shelter staff. Funeral directors. Grave diggers.

Suddenly these disparate occupations were unified under a whole new category: Essential workers. These people on the front lines — many of them previously undervalued and even invisible — were hailed as heroes. Supermarket employees were mentioned in the same breath as physicians. Signs went up thanking them for their service. Some even got temporary raises.

Advertisement

Nine months later, the praise has largely dried up, and most of the pay hikes are long gone. But they are still out there performing crucial work, dealing with the public behind masks and gloves and face shields as the virus continues to rage, putting themselves at risk so everyone lucky enough to be able to do their jobs from home can stay put.

Many essential workers are immigrants and people of color making minimum wage, or close to it, who are at higher risk of catching COVID-19. Some of them live in communities with elevated rates of infection — in part because there are so many essential workers living in them. Just look at the Massachusetts cities with the highest rates of positive COVID-19 tests: Chelsea, Everett, Lawrence, Lynn, and Revere. All are home to large populations of people of color, and, according to the UMass Donahue Institute, all have about half of their working population employed on the front lines. A Walmart in Worcester, another city with a high infection rate and many front-line workers, was the site of one of the state’s largest outbreaks, with 81 employees testing positive.

Advertisement

The sacrifices these workers are making are monumental. Boston Medical Center, the city’s safety net hospital, has been at the center of the coronavirus storm. At one point last April, 7 out of 10 patients were seriously ill with COVID-19, and the hospital’s intensive-care beds were full. Surgeons were volunteering to be internists. Nurses were sweating through layers of heavy protective gear and holding hands with people as they died. Genta Baci, a family medicine doctor there, rented an apartment to keep from infecting her family. Others sent their children to live with relatives or isolated themselves in their rooms; some stopped holding hands during premeal prayers. Especially in the early days, countless essential workers spoke of stripping off their clothes in the garage when they got home from work and heading straight to the shower.

Maria Colville, a 59-year-old personal care attendant in Cambridge, lost work from two regular clients during the pandemic, including one who feared getting infected, but kept caring for a disabled woman in Watertown. “Doing nothing in a crisis is not an option,” she says. But a temporary 10 percent raise and unemployment benefits was not enough to keep Colville and her husband from relying on food pantries and maxing out their credit cards. And, to her, the praise for essential workers rang somewhat hollow. “A lot of that ‘thank you’ is over the fact that, ‘if you don’t do it, who am I going to get to do it?’” she says.

Advertisement

As the holiday shopping season kicked off amid a renewed surge in virus cases, a national group of essential retail workers backed by the advocacy group United for Respect unveiled a platform demanding an additional $5 an hour, along with paid leave and better safety precautions. Gig workers, many of whom are among the ranks of the essential, shopping for supplies and delivering meals, still don’t have access to employer-provided health care or guaranteed paid sick time.

These are workers who take pride in the increased reliance on their services. One Waltham Uber Eats driver saw herself and her fellow delivery drivers as a “huge infrastructure” bringing food to people so that they could stay safe at home. The pandemic made one Falmouth Instacart shopper feel like she was filling a vital role for the first time. “I never thought that I would be considered an essential, important person,” she said in April. But “if I do five deliveries a day, that’s five people who didn’t have to go to the store. . . . It’s five people who could have gotten sick.”

Dan Natale, produce manager at Stop & Shop in Seekonk, doesn’t mind that the adulation has died down. “I like the term ‘essential,’ but in a way, we all are,” he says. “We’re all cogs in a bigger machine.”

Advertisement

But even temporary recognition could have a lasting impact, says Molly Kinder, a fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies essential workers. And that could lead to permanent improvements, like higher pay and better safety measures.

“Society can’t un-see what we’ve seen,” Kinder says. “As more privileged Americans hunkered down and safely worked from home and suddenly relied on a front-line workforce that they maybe never paid attention to, I think there was a new sense that, ‘Wow, my life, I couldn’t go on without these workers . . . and they’re sacrificing so much.’”

2020 BOSTONIANS OF THE YEAR

The Front Line

The Front Line

In 2020, they stood up to fight the twin pandemics of COVID-19 and racial injustice. Meet the people leading us through a harrowing year.

THE COVID SCIENTISTS

Stacey Gabriel and the Broad Institute, plus Galit Alter, Lindsey Baden, and Ashish Jha

THE SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCATES

Monica Cannon-Grant, Queen-Cheyenne Wade, Segun Idowu, and Sofia Meadows

THE COMMUNITY LEADERS

Gladys Vega and La Colaborativa

THE ESSENTIAL WORKERS

Health care workers, grocery store employees, delivery drivers, and so many more

THE HUNGER FIGHTERS

Erin McAleer and Project Bread

THE ROLE MODEL

Jaylen Brown, activist and athlete

Katie Johnston can be reached at katie.johnston@globe.com. Follow her @ktkjohnston.