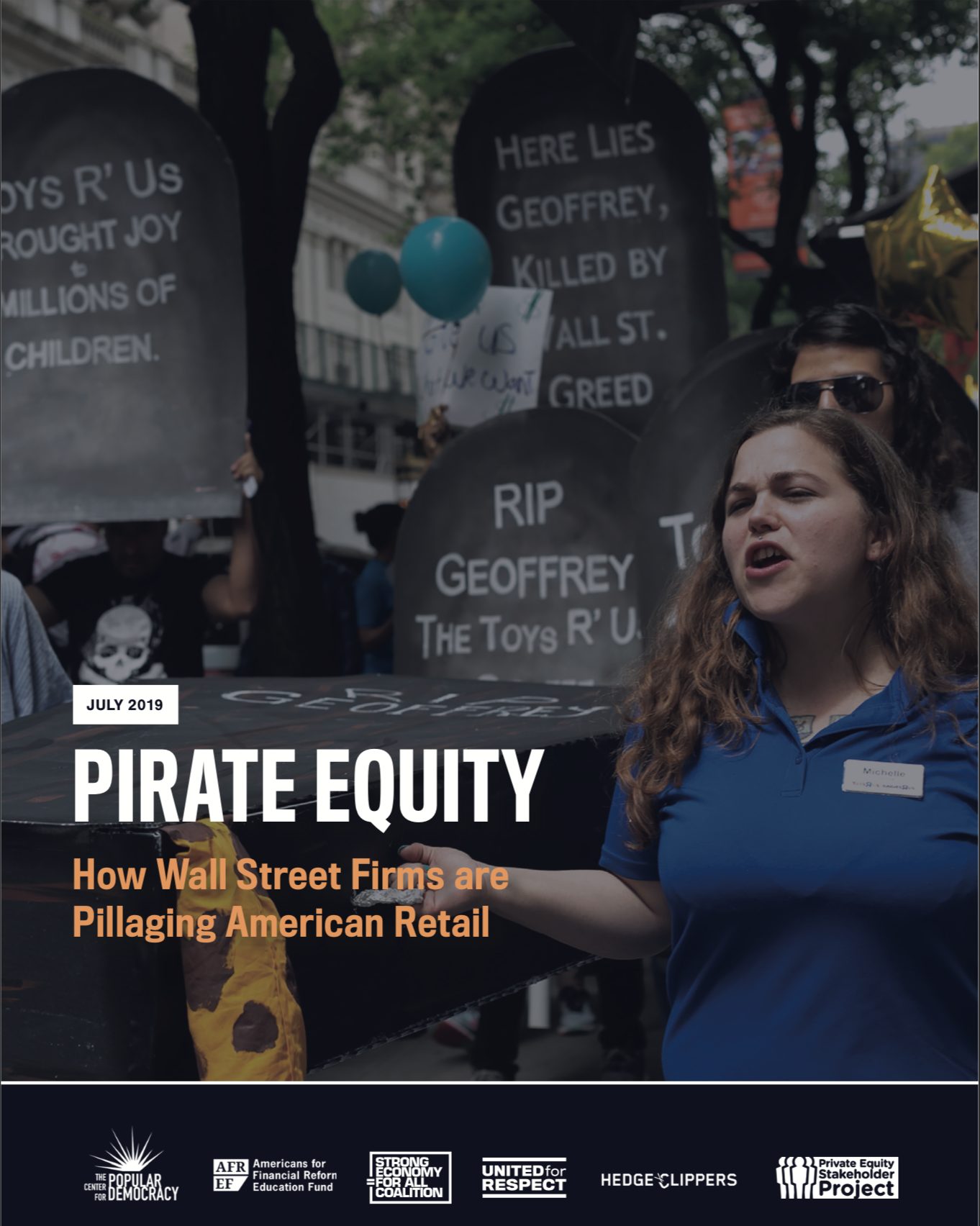

Executive Summary

For decades, Wall Street firms have been driving economic inequality in our country, threatening working people’s livelihoods, and destabilizing local economies. Today, private equity firms own companies that employ more than 5.8 million Americans.

In the last decade alone, private equity firms and hedge funds have made substantial controlling investments in over 80 major retail companies, which has drastically impacted the sector. Given that private equity-owned companies are twice as likely to go bankrupt as public companies, it is unsurprising that 10 out of the 14 largest retail chain bankruptcies since 2012 were at private equity-acquired chains.

This original analysis reveals that in the last 10 years, a staggering 597,000 people working at retail companies owned by private equity firms and hedge funds have lost their jobs. An estimated additional 728,000 indirect jobs have been lost at suppliers and local businesses, meaning Wall Street’s gamble on retail has led to more than 1.3 million job losses in total.

Wall Street firms are poised to impact an additional one million people working in retail in the coming years.

Risky private equity deals have far-ranging impacts on working families and local economies: working people face sudden unemployment and protracted financial hardship; private equity owners often use the bankruptcy process to dump their obligations to current and future retirees; pension funds, which make up the largest investor group for private equity deals, see poor investment returns after private equity-owned retailers go bankrupt; and retail bankruptcies directly reduce the tax bases of states and localities.

Wall Street executives exploit gaps in laws and regulations, and lucrative loopholes, to amass huge profits at the expense of working people and local communities. These massive profits pay for luxurious lifestyles for fund managers and their families, while workers and their families and communities face real hardship.

Key Findings

WALL STREET’S GAMBLE ON RETAIL HAS LED TO MORE THAN 1.3 MILLION JOB LOSSES:

- Original analysis reveals that in the last 10 years, 597,000 people working at retail companies owned by private equity firms and hedge funds have lost their jobs. These retail layoffs occurred while the total retail industry added over one million additional retail jobs during the same period.

- Wall Street firms have destroyed eight times as many retail jobs as they have created in the past decade.

- This has ripple effects felt far beyond those retailers and their employees. Bankruptcies and store closures at retailers have also spurred layoffs at suppliers, multiplying job losses. When 100 direct jobs are lost at retailers, 122 additional indirect jobs are lost. So beyond the 597,000 people who directly lost their jobs, an estimated additional 728,000 indirect jobs have been lost.

- That means Wall Street’s gamble on retail has led to more than 1.3 million total job losses.

WALL STREET IS POISED TO IMPACT EVEN MORE WORKING PEOPLE IN THE COMING YEARS:

- Our analysis shows that over one million retail workers are at risk of losing their jobs in the future. These individuals currently working at 80 private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers face an uncertain future if current trends continue.

WALL STREET’S RISKY DEALS HAVE FAR RANGING IMPACTS ON WORKING FAMILIES AND LOCAL ECONOMIES:

- Beyond the direct and indirect impact on jobs of retail closures, Wall Street owners have been quick to use the bankruptcy process to dump their obligations to current and future retirees.

- In addition, since pension funds make up the largest investor group for private equity, retail bankruptcies have negatively impacted pension funds’ investment returns, harming retirees.

- Failures at private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers have also directly reduced the tax bases of states and localities.

WALL STREET EXPLOITS A RANGE OF LUCRATIVE TAX LOOPHOLES AND BANKRUPTCY CODE MANIPULATIONS TO BOOST PROFITS AND AVOID REGULATIONS:

- Despite being some of the wealthiest people in the country, private equity and hedge fund managers use a number of tax giveaways, including the carried interest loophole, which allow them to pay taxes at a lower rate than many working Americans.

- Wall Street firms also benefit from a revolving door between the financial sector and the government agencies tasked with regulating it.

WALL STREET FIRMS HAVE BEEN KEY DRIVERS OF ECONOMIC INEQUALITY:

- Private equity and hedge fund managers insulate themselves from loss, enjoy lucrative fee structures, and pursue an aggressive tax avoidance strategy which enables them to reap massive profits.

- Dozens of private equity executives have become billionaires and thousands more have become extremely wealthy. The top 25 hedge fund managers make an average of $850 million per year, and several fund managers are profiled in this report.

- These same Wall Street actors enrich themselves while lowering workers’ wages and benefits. Given one in four retail workers live in or near the poverty threshold — a proportion that is even higher for Black or Latinx retail workers at 4 in 10 because of discriminatory practices and occupational segregation — Wall Street-driven wage cuts and job losses have devastating impacts families.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The report findings highlight the urgent need to advance federal policy solutions in 2019 that:

Regulate private equity firms and hedge funds in order to curb the high-risk financial practices that extract wealth from our economy and destabilize employers.

Protect communities and pension funds that provide tax incentives for or invest in private equity and hedge funds with transparency and accountability regulations and the resources needed for active enforcement of existing policies.

Strengthen the rights of employees when their companies file for bankruptcy, including making it more difficult for creditors to push companies into liquidation instead of reorganization, strengthening the position of employees as stakeholders in the bankruptcy process, and guaranteeing severance pay and other benefits.

Prevent private equity and hedge funds from draining value from companies they own through stock buy backs, capital distributions, and fees that divert resources away from the business and jobs.

Build public momentum for employee representation at private equity and hedge fund-owned companies for more robust and accountable corporate governance.

Make private equity and hedge fund managers pay a higher share in corporate taxes for reinvestment in communities and the social safety net.

INTRODUCTION

Private equity has long been under fire for exacerbating growing economic inequality at the expense of working people as they reap massive profits for executives. With big pockets and outsized political influence, private equity firms have forced a seismic shift in how American businesses are run as they reshape companies and industries to fit their need to extract large profits quickly. From retail to healthcare to manufacturing, private equity firms own, control, and manage an increasingly large number of companies. Prior to the global financial crisis, private equity firms managed around $1 trillion in assets, with investors ranging from public pension funds to university endowments. Today, these firms manage more than $5 trillion in assets and own almost 8,000 U.S. companies. Moreover, today, private equity firms own companies that employ more than 5.8 million Americans.

In the last decade, both private equity firms and hedge funds have rapidly expanded into retail, acquiring over 80 major retailers. These risky deals have led to bankruptcies and significant job losses which have had far-ranging impacts on working families and local economies. In the last decade, Wall Street’s gamble on retail has led to more than 1.3 million job losses. The stakes are high for the additional one million people currently working at private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers. This report underscores the need to regulate private equity firms and hedge funds to prevent risky financial practices while strengthening the rights of working families and protecting local communities.

Part I of this report explains how private equity firms and debt financing deals work, including perverse incentives that encourage excessive risk-taking by Wall Street executives at the expense of working people. Part II unveils new, original data on the number of retail jobs destroyed at Wall Street-owned retailers over the last ten years, as well as estimates of the number of additional workers at risk of losing their jobs to Wall Street-driven bankruptcies in the future. Part III traces the financial sector’s damaging expansion into retail that resulted in these job losses, as well as the ways in which private equity and hedge fund managers have exacerbated inequality in the retail sector and beyond. Part IV moves beyond job losses to explore the damaging ripple effects the wave of retail bankruptcies is having on state and local economies. The final section of the report explores how we got here — including the tax loopholes and regulatory weaknesses that have enabled private equity to explosively expand in recent years — while underscoring the urgent need for strengthened regulations.

Debbie Mizen lives in Youngstown, Ohio, and began working at Toys “R” Us in 1987. She was a single mother when she started working and was able to care for her three children on her modest salary. Debbie was an assistant manager for the last 12 years of her career, although she knew she was earning less than male supervisors in the same position. In June 2018, she lost a job she loved when Toys “R” Us liquidated and closed over 800 stores across the country. Debbie found out that her store was closing on same day as her mother’s funeral and was devastated. Since her store closed, she has faced unemployment. When her unemployment checks ran out, she had to take a job in a grocery store collecting grocery deliveries for customers while earning half of what she did at Toys “R” Us. She is turning 67 this year.

PART I

While Wall Street private equity firms wield enormous power and influence over our economy, their business practices are not widely understood. Part I will provide an overview of private equity firms, including how they are structured and how they use debt financing and leveraged buyouts to amass enormous profits. This section also highlights the perverse incentives shaping their business decisions which create a high risk/low reward situation for working people.

While the report primarily refers to private equity, the data analysis also includes hedge funds that own US retailers. There is a more of a grey area than a clear divide between private equity and hedge funds. For the purposes of this report, the critical distinction is not the name of the fund but the investment strategy that is used. This report examines funds that take control of companies and use their control rights to drain value from the companies in ways that negatively affect the sustainability of the firm and its relationship to workers and communities. Taking control of companies is an investment strategy typically associated with private equity firms, but nothing stops hedge funds from owning companies and many have pursued this strategy. However, this report does not address investment strategies that involve short-term market speculation that do not involve control of companies, which is a strategy more typically associated with hedge funds.

PRIVATE EQUITY: WALL STREET’S SHADOW BANKING SYSTEM

Private equity firms are Wall Street investment companies that raise money from pension funds, endowments, hedge funds, and wealthy individuals in order to acquire companies. Private equity managers often claim they will quickly fix these companies and make them more profitable. Then, the private equity firms will sell the newly profitable company or take it public on the stock exchange. They typically plan to resell a company within five years and promise high returns to investors in the process.

In practice, these Wall Street firms make sweeping changes to cut costs and boost profits, including pay freezes, layoffs, and store closures. Private equity firms often take control of boards and appoint new leadership at companies. One study found that nearly 70 percent of CEOs are replaced at some point during private equity ownership (typically a 3 to 5 year ownership window); whereas average CEO tenure in the US is seven years.

In the retail industry, both private equity firms and hedge funds have made substantial controlling investments in major companies over the last several years. Private equity and hedge fund- owned retailers employ more than 1 million of the 15.8 million retail workers nationwide. A wave of high-profile retail bankruptcies in the last few years — including household names like RadioShack, Toys “R” Us, Sports Authority, Payless ShoeSource, Sears, and Kmart — have impacted retailers owned by Wall Street.

THE RISE OF “DEBT FINANCING” AND LEVERAGED BUYOUTS

Private equity has seized retail targets through risky investment deals called leveraged buyouts (LBOs) that saddle retailers with high debt and can instigate sweeping changes, including pay cuts and store closures. The first part of a leveraged buyout (LBO) is not unlike the process of buying a home. When a family buys a house they make a downpayment and use mortgage financing to pay back the home loan over time. However, the critical LBO difference is that when a private equity firm acquires a company, it makes a downpayment with money from investors and then requires the target company to take out the loans needed to finance the deal. That means the companies, not the private equity firms, are responsible for repaying the debt. The only money that private equity firms have at stake is their initial down payment equity investment (this is often only a third or less of the total cost to acquire the company). Most of this investment comes from limited partners who are the outside investors to the private equity fund. It is frequently the case that the general partners who actually control the private equity firm only contribute 1 to 2 percent of the equity that’s required for the leveraged buyout.

HIGH RISK/LOW REWARD FOR WORKING PEOPLE

Leveraged buyouts are structured so that private equity firms can reap the biggest benefits with limited personal risk. This deal structure offers private equity managers perverse incentives that encourage short-termism and excessive risk taking, generally at the expense of the employees of acquired portfolio companies. While public companies usually get about 30% of their capital from debt, private equity-owned businesses operate with about 70% debt. The use of large amounts of debt in private equity acquisitions has been a major driver of the growth in excessive corporate debt, which regulators have cited as a dangerous amplifier of the next recession. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently found that over half of leveraged lending in 2018 was acquisition-related.

Private equity firms contend that these unusually high debts will impose discipline on managers and force accountability on companies that will benefit from private equity managers’ close monitoring and oversight. However, this debt arrangement is actually a low-risk and high- reward setup for these Wall Street firms. It incentivizes excessive risk-taking by private equity managers at the expense of the acquired company. If the private equity firm drives a company into bankruptcy, the loss for the private equity firm is limited; it is the company and its workers who pay the price. Because the company — rather than the private equity firm — is actually on the hook for the debt, workers, vendors, and institutional investors are left trying to negotiate over whatever remains after the company covers its debt payments.

Despite these serious risks, private equity has thrived for decades thanks to lax regulation and tax loopholes that favor its business model. Private equity managers have deployed their massive wealth to exert considerable political influence to maintain these unfair advantages. They benefit from a lack of transparency around their business operations and fee structures, as well as a revolving door between the government and private equity firms. Private equity managers have secured powerful regulatory roles within the government and later left those roles to return to the financial sector. (For instance, immediately before becoming Commerce Secretary, Wilbur Ross previously spent 17 years at WL Ross & Co, a private equity fund he founded.) Without sufficient regulation and government oversight, private equity firms have been emboldened to take excessive risks. These risky deals threaten the stability of our economy, compound inequality, and gamble with the livelihoods of millions of working people.

WALL STREET IS DRIVING THE RECENT WAVE OF RETAIL BANKRUPTCIES

Private equity’s expansion into retail has been followed by wide scale job losses that have devastated working families and destabilized our economy. There have been a growing number of high-profile retail bankruptcies and store closures. In the past five years, dozens of major retailers have gone bankrupt. While many point to the rise of e-commerce and competition from Amazon hurting the retail industry, this simplistic analysis overlooks the destabilizing impact of Wall Street takeovers of retail brands. Eileen Appelbaum, from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, and Rosemary Batt, a professor at Cornell University who studies management and employment relations, cite findings that the high amounts of debt in a typical private equity deal lead to higher rates of bankruptcy. Across all sectors, private equity-owned companies are twice as likely to go bankrupt as public companies.

Private equity firms owned a considerable majority of retailers that have gone into bankruptcy. Ten out of the 14 (or 71 percent) of the largest retail chain bankruptcies since 2012 were at private equity-acquired chains. Among the retailers that filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2016 and 2017, two-thirds were backed by private equity.

*Store closures in first three months of 2019

Mary Osman worked at Toys “R” Us in Boardman, Ohio, for 24 years where she was a cashier. In 2016 she lost her benefits and continued working part-time at Toys “R” Us, relying on her husband for health insurance. She lost her job at Toys “R” Us when the company liquidated in 2018 and closed all of its stores — over 800 — across the country. Mary had planned to work at Toys “R” Us for three years before retiring with her husband. Since her store closed, Mary has been unemployed. Her husband has continued working to support both of them. Mary is also relying on social security to make ends meet. Prior to the Toys “R” Us bankruptcy Mary was looking forward to retirement in a few years. She instead finds herself at the bottom of the career ladder, competing with much younger applicants for incredibly labor-intensive positions.

PART II

WALL STREET IS A JOB KILLER

Private equity firms have a demonstrated record of destroying jobs while claiming to create economic growth. Private equity-owned companies cut jobs and lay off employees in order to increase cash flow or shut down entirely due to crushing debt loads. A National Bureau of Economic Research analysis of over 3,000 private equity acquisitions found that retail companies acquired by private equity experienced a 12 percent drop in employment over the subsequent five years.

WALL STREET’S ROLE IN RETAIL BANKRUPTCY AND JOB LOSS

Our original analysis to measure the impact of Wall Street on retail bankruptcy and job loss finds that a staggering 597,000 people working at private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers have lost their jobs in the last 10 years after their Wall Street-managed retailers went bankrupt or liquidated. These retail layoffs are especially troubling because they occurred while the retail industry added over one million additional jobs during the same period. Over the same period, private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers added only around 76,000 jobs — creating only one job for every eight jobs that were eliminated — meaning that Wall Street cost the retail sector over half a million (521,000) in net job losses. These job losses spanned over 25 retailers, including household names like Sears, Toys “R” Us, Payless, Sports Authority, Claire’s, and RadioShack.

INDIRECT JOB LOSS: EFFECTS OF RETAIL BANKRUPTCIES FELT BEYOND RETAILERS

These job losses devastate local economies and ultimately ripple throughout the national economy as suppliers and local small businesses feel the downstream effects. Not only have private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers laid off hundreds of thousands of workers, the Wall Street-driven retail bankruptcies also have effects that are felt far beyond those retailers and their former employees. Businesses and their workers, including in the retail sector, not only provide direct jobs but also have multiplier effects on indirect jobs; in other words, their economic activity supports workers in other industries, such as those who manufacture and deliver the products sold at retailers and businesses where retail employees spend their income, like grocery stores or gas stations.

Private equity-owned retailers’ suppliers and their employees suffer when the retailers go bankrupt, close stores, or shut down completely. For example in July 2018, just months after Toys “R” Us shut down, Mattel, the maker of Barbie and Hot Wheels, announced it was laying off 2,200 workers after its sales dropped by 14 percent. Then, in October 2018, toymaker Hasbro — which produces Play-Doh, Transformers, and My Little Pony toys — announced it would lay off up to 10% of its employees. Hasbro’s sales fell 12% in the third quarter 2018, a drop the company attributed primarily to the loss of Toys “R” Us.

A January 2019 study by the Economic Policy Institute noted that for every 100 direct jobs lost at retailers, approximately 122 additional indirect jobs are lost. Over the past decade, the 597,000 documented direct retail job losses have caused an estimated additional 728,000 indirect-job losses, meaning Wall Street’s gamble in retail has likely cost more than 1.3 million total job losses.

WOMEN AND PEOPLE OF COLOR HARDEST HIT BY JOB LOSSES

Wall Street has eliminated jobs across the retail industry but layoffs were most concentrated in the clothing, general merchandise, and grocery subsectors. Given the workforce demographics of those subsectors and the dynamics of the broader economy, these job losses disproportionately impact a diverse workforce with large numbers of women and people of color. For instance, more than three-quarters (76%) of workers in the retail clothing sector are women, and 43% are Black, Asian, or Latinx. In the general merchandise sector, nearly half of workers (46%) are Black, Asian, or Latinx, and 60% are women.

These job losses are especially devastating for people working in retail because they already face high rates of poverty and income volatility. Retail employers often provide poor quality jobs with low pay and no benefits, stagnant wages, high rates of underemployment (despite many workers wanting full-time hours), and unstable schedules that fluctuate week to week. As a result, one out of four retail workers live below or near the poverty level. Retail workers of color face high rates of occupational segregation and are concentrated in the retail jobs and sub sectors with the lowest pay and limited mobility (such as cashier positions in apparel). Faced with poor job quality and widespread racial discrimination, very high numbers of retail workers of color — two out of five of Black (43%) and Latinx (42%) — live in or near poverty.

Half of retail workers experience income volatility from week to week due to unpredictable schedules. This income volatility makes saving difficult and decreases the likelihood that people will have a cushion to weather sudden unemployment. Since 40% of Americans cannot cover a $400 emergency expense, private-equity-driven job losses add significant financial precariousness for impacted workers. Finally, 65% of people working in retail have a child in their home, which brings added urgency to securing reliable income.

The effects of unemployment can be significant and long-lasting, especially for Black and Latinx workers who have a harder time rebounding and face employment discrimination in the job search process. People who lose their jobs after private equity and hedge fund acquisitions must navigate a labor market rife with racial disparities. Black unemployment is consistently twice the rate of white unemployment due to a host of discriminatory systems and practices by hiring managers. Biased decisions and systemic barriers negatively impact the job prospects of applicants of color. Black workers are disproportionately represented in the share of long-term unemployed and discouraged workers, despite having looked for work.

Sad’e Davis lived across the street from her Toys “R” Us in Van Nuys, California, and was a loyal customer for many years before getting hired as an associate. As a single mother of two daughters who had to work multiple jobs to get by, Sad’e felt like Toys “R” Us was a home away from home. Her coworkers were like a second family. However, after four years with the company, Sad’e was laid off during liquidation. She was forced to survive with the income from her remaining job at Burlington Coat Factory, while supporting her two daughters and taking care of her grandmother and disabled mother. She now lives in uncertainty — knowing her job could be stolen by Wall Street greed at any moment.

WALL STREET IS POISED TO FURTHER HURT RETAIL WORKERS IN THE FUTURE

In light of Wall Street’s track record of destroying retail jobs, how many working people will be impacted moving forward? Private equity firms and hedge funds have already cost over half a million net retail jobs over the past decade, but over a million additional retail workers remain at risk of losing their jobs as a result of Wall Street in the coming years based on our analysis.

OVER ONE MILLION RETAIL WORKERS ARE AT RISK OF LOSING THEIR JOBS IN THE FUTURE.

These potentially vulnerable workers currently are employed at nearly 50 retail companies owned by private equity firms and hedge funds. The record of Wall Street-driven waves of store closures, layoffs, and bankruptcies combined with the high levels of debt suggests that the odds are not in these workers’ favor.

Working people must navigate an increasingly uncertain retail industry over the coming years. The prices of companies are soaring and many deals being made today are bigger and involve more debt than before the financial crisis, despite warnings from regulators on the dangers of excess leverage. Although private equity firms are raising more money than they can spend — a record $1.1 trillion in cash from investors in 2017 — these firms still heavily rely on debt financing. In fact, leveraged buyouts were up 27 percent that year. This echoes the private equity takeover boom before the 2008 financial crisis, with industry analysts increasingly seeing private equity as the next risky debt bubble. Moody’s Analytics predicted a wave of new retail bankruptcies when a large number of debts come due in 2019 and 2020. While $1.9 billion of retail debt matured in 2018, from 2019 to 2025 that will rise to an annual average of nearly $5 billion. In May 2019, the Federal Reserve called for continued vigilance “as the share of new leveraged loans going to the riskiest firms reached its highest level in the first quarter since bank regulators cracked down on such lending in 2013.” A recent Federal Reserve report on financial stability found that 40 percent of new loans to companies with high debts went to companies whose debt is more than six times their earnings.

Veronica Sanchez worked at a Gymboree call center in Dixon, California, for 15 years. After Gymboree announced liquidation, Veronica was disappointed to be losing her job. While her former coworkers received severance pay in previous rounds of layoffs and during Gymboree’s first bankruptcy, Veronica and her coworkers received nothing. News sources later reported that Gymboree had changed their severance pay policy on the same day that the company announced bankruptcy. Since losing her job, Veronica has had to cash out her 401k because she can’t survive solely on her unemployment check. She’s started studying to be a Medical Assistant because she doesn’t want to work in retail again.

WALL STREET’S GROWING DOMINANCE IN RETAIL

The retail industry is undergoing a rapid transformation. With the rise of behemoths like Amazon and the collapse of well-known brands like Toys “R” Us, retail is being shaped by several major forces:

A SHARP INCREASE IN CORPORATE CONCENTRATION.

THE EMERGENCE OF NEW TECHNOLOGY.

THE GROWING DOMINANCE OF WALL STREET AND THE FINANCIAL SECTOR OVER THE REAL ECONOMY AND WORKING PEOPLE’S LIVES.

PART III

WHY HAS WALL STREET ACQUIRED SO MANY RETAILERS?

Retail is a highly variable industry that rises and falls with changing consumer demand. The industry often operates at low profit margins with little room for error. Retailers traditionally held only small amounts of debt and owned all or most of their stores and retail floor space. This real estate asset cushion allowed retailers to survive the ups and downs of consumer demand and market volatility.

At first glance, the unpredictability of retail earnings makes the industry a puzzling target for private equity leveraged buyouts. However, retail companies can be attractive to private equity because retail chains often own some or all of their store property. These retail real estate assets can better secure the debt taken on during private equity LBO deals. Private equity firms will also often sell off an acquired company’s real estate assets when it’s advantageous to the private equity firm. In turn, that often requires the companies to then lease back the same buildings they previously owned. In addition, retailers generate high amounts of cash which enables them to cover the payments on the debt from leveraged buyouts. This ensures private equity profits regardless of the retail chain’s success, but it often puts retail companies in a financially precarious position. Private equity firms have often sought to extract cash from retailers through dividend recapitalizations — where the retailer takes on more debt to pay dividends to its private equity owner. For instance, the two private equity firms that acquired Payless Shoes paid their own firms $700 million in dividends in 2012 and 2013, but Payless later filed for bankruptcy because of its crippling debt load.

Wall Street firms in retail prioritize short-term financial returns. This short-termism makes them willing to extract fees and dividends from companies they acquire, with minimal regard for workers and at the expense of the long-term viability of the company. Under private equity management, boards have increased CEO pay but refused to offer wage increases for workers. One study measuring the impact of over 3,000 private equity acquisitions found that in the two years after a leveraged buyout, workers’ wages fell even though productivity rose.

DRIVER OF INEQUALITY: EARNING BILLIONS WHILE LIMITING WAGE INCREASES FOR WORKERS

Wall Street drives economic inequality in significant ways. Private equity and hedge fund managers are insulated from loss, enjoy lucrative fee structures, and pursue an aggressive tax avoidance strategy which enables them to reap massive profits. Dozens of private equity executives have become billionaires and thousands more have become extremely wealthy. One analysis of the annual earnings of six private equity firm executives found that private equity firms earn almost ten times as much as banking CEOs with average earnings were over $211,000,000 per year. Some like Stephen Schwarzman from Blackstone Group earn nearly $800,000,000 per year. The top 25 hedge fund managers make an average of $850 million per year — 100% of these hedge fund managers are men and 100% are white.

These same Wall Street actors enrich themselves while lowering workers’ wages and benefits. Private equity managers have an incentive to squeeze more cash flow out of firms in a relatively short period of time (within 3 to 5 years). Multiple studies have shown that private equity ownership generally depresses the wages and benefits of employees at their portfolio companies. Given that employers already pay workers of color less than they pay white workers — for every dollar earned by white men, Latina women take home only 62 cents and Black women take home only 68 cents, for example — these wage decreases disproportionately harm workers of color.

Racial wealth disparities are even more pronounced. Average wealth of white families was $919,336 in 2016, compared to $191,727 for Latinx families and $139,523 for Black families. This racial wealth gap has resulted from recent and historic policies and practices that stripped wealth from Black people and gave wealth to white people. And, the racial wealth divide is growing. In the ten years since the Great Recession, average white wealth has risen by over $116,000 since the Great Recession, while average Black wealth has fallen by $16,762 and average Latinx wealth has fallen by $23,807.90. Private equity and hedge fund managers’ vast accumulation of wealth, combined with decisions to limit wage increases and benefits for employees at acquired companies, makes the industry one of the most efficient private drivers of inequality in the world today.

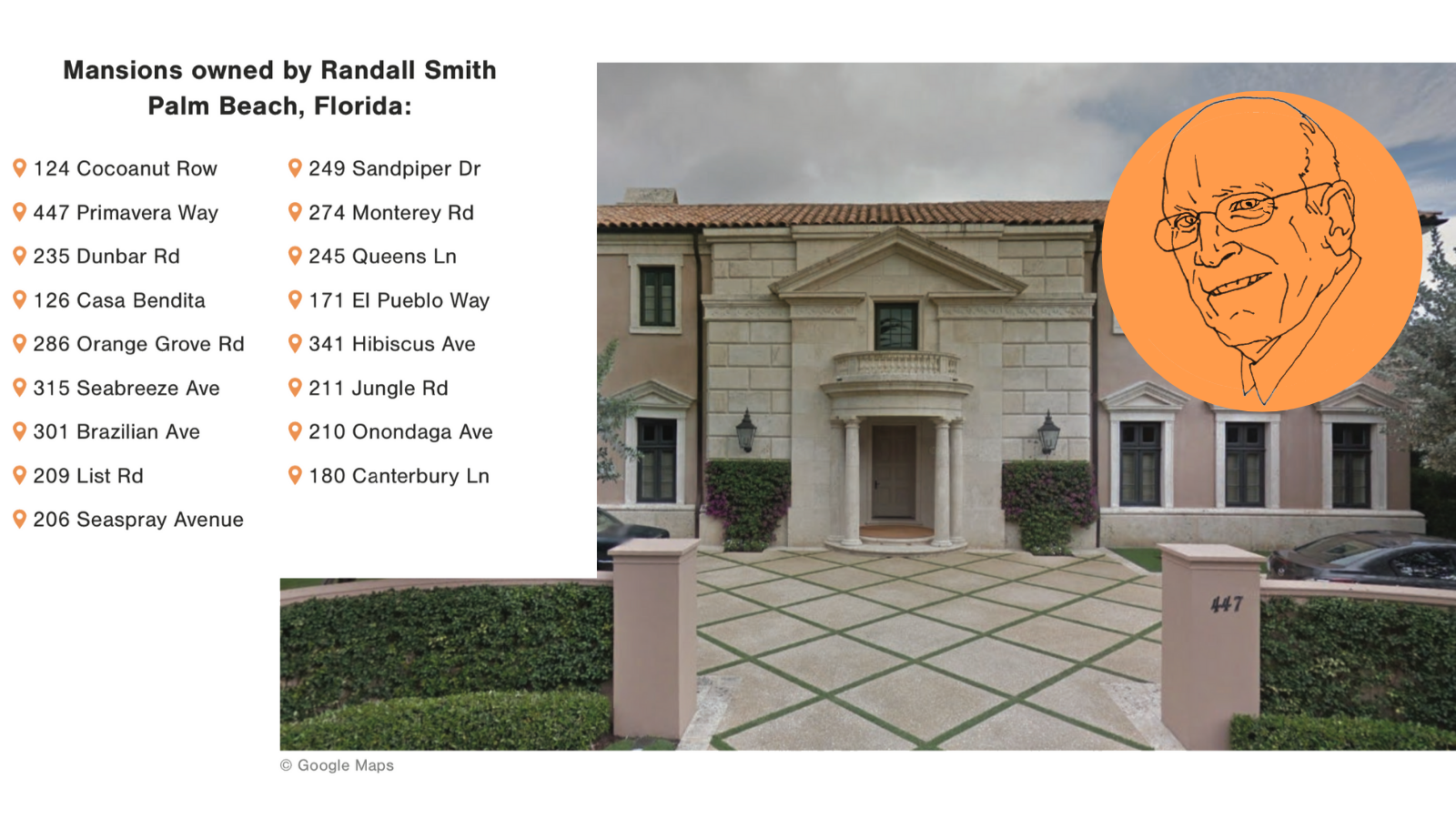

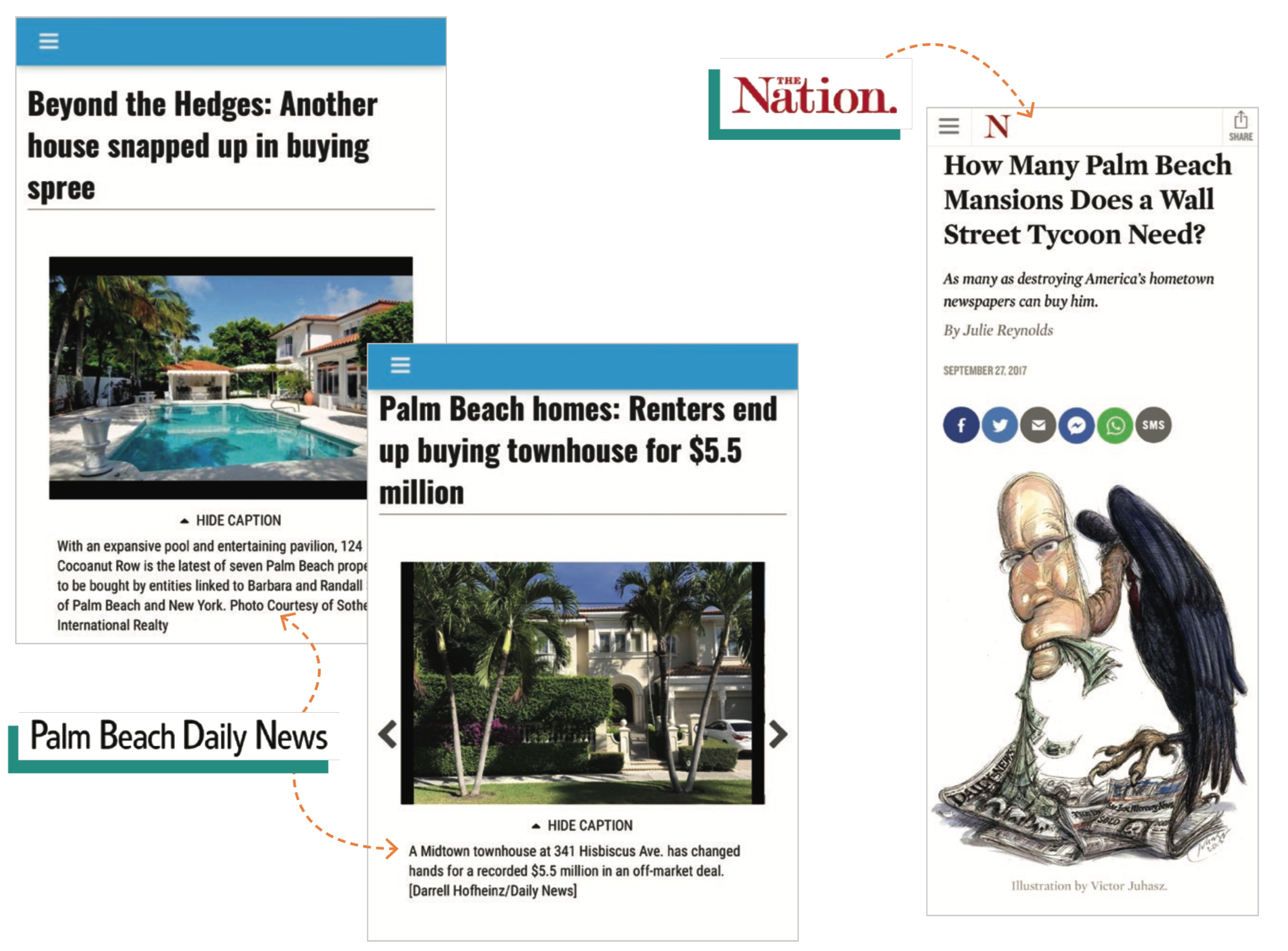

ALDEN GLOBAL CAPITAL’S RANDALL SMITH SPENDS BIG WHILE SEARS PENSIONERS STRUGGLE

Randall Smith is the founder, owner, and chief of investments of Alden Global Capital — the hedge fund controlling Payless Shoesource, which recently announced that it will liquidate. Smith’s net worth — likely hundreds of millions of dollars — is hard to trace because he prefers to shield his assets by using limited liability companies (or LLCs) and headquartering many of his companies offshore, often in known tax havens, such as the Isle of Jersey and the Cayman Islands. Journalists and researchers nonetheless have demonstrated Smith’s immense wealth that has been built off of a business model often referred to as “vulture” capitalism. For example, from 2013 to 2014, Smith purchased sixteen mansions in Palm Beach, Florida, for approximately $57.2 million (all through LLCs). While Smith has since sold at least one of these properties, he and his wife may have owned as many as eighteen multi-million dollar properties in Palm Beach and the Hamptons, New York, at one time.

Alden’s president, Heath Freeman, bought a $4.8 million waterfront mansion on two acres in East Hampton, New York. After purchasing the multimillion dollar home, he built a large addition and purchased the pond next to the property. In 2014, Freeman paid nearly $120,000 for the basketball jersey worn by Christian Laettner when he made the iconic game-winning shot for Duke University against the University of Kentucky to take Duke to the Final Four in the 1992 NCAA Tournament.

Meanwhile, Smith and Freeman’s Alden Global Capital manages approximately $2 billion in assets. Smith and Alden are considered “vultures” because of the types of predatory and ruthless strategies they have used in the past to dismantle retailers, including, most recently, Payless Shoes. Alden has been accused of mismanaging its retail holdings, appointing managers who sell off assets and slash costs without concern for companies’ continuing profitability, its workers, or its creditors. In 2018, Alden gave Payless a $45 million loan which did not improve the company’s financial outlook but, according to Payless creditors, allowed “the hedge fund to get ahead of other lenders seeking repayment in the new bankruptcy.” Recently, Payless creditors flagged serious conflicts of interest between Alden and Payless, which led a bankruptcy judge to appoint a monitor to oversee the Payless board. The Payless board has three board members with direct ties to Alden, including Freeman. Payless sought $84,000 per month to pay the Alden-controlled board during bankruptcy proceedings.

Alden’s disruption of the media, especially the newspaper, industry is another example. As a majority owner of Digital First Media (DFM), which is the second largest newspaper chain in the US, Alden owns hundreds of newspapers and other news outlets around the United States. These newspapers include some larger market dailies, such as the Denver Post. They often purchase the newspapers then dramatically slash costs, including laying off many of the editors, journalists, and photographers, and often selling their real estate and other assets. While job cuts are an industry-wide problem, outlets owned by DFM cut staff at twice the industry rate. Between 2011 and 2018, DFM-owned outlets cut two out of every three staff positions, while Alden extracted at least $241 million in cash from DFM, borrowed another $248.5 million from newspaper workers’ pension funds, and saddled the newspapers with another $200 million in debt. The Denver Post, in an unusually highly critical editorial of its owner, described this as “a cynical strategy of constantly reducing the amount and quality of its offerings,” which would soon reduce the newspaper to “rotting bones.”

Kathy Cagle was laid off from Sears in Newark, California, in October 2018, during the same month that Sears filed for bankruptcy. After working full-time at Sears for 29 years, Kathy was promised ten weeks of medical insurance and eight weeks of severance pay if she stayed until the last day her store was open. However, as the weeks went by after the store closed, Kathy and her coworkers didn’t hear anything about their severance. During that time, Kathy went to the doctor and was told that her medical insurance had been cut off. She and her coworkers contacted Sears and eventually found out that they would not be receiving their severance as promised because of the bankruptcy. Prior to the bankruptcy, working at Sears offered a pathway to financial security for Kathy. She was able to buy a home in the Bay Area and put her daughter through college. After having her livelihood taken away, as well as the safety net of her severance, she has struggled to cover bills and her daughter’s college expenses.

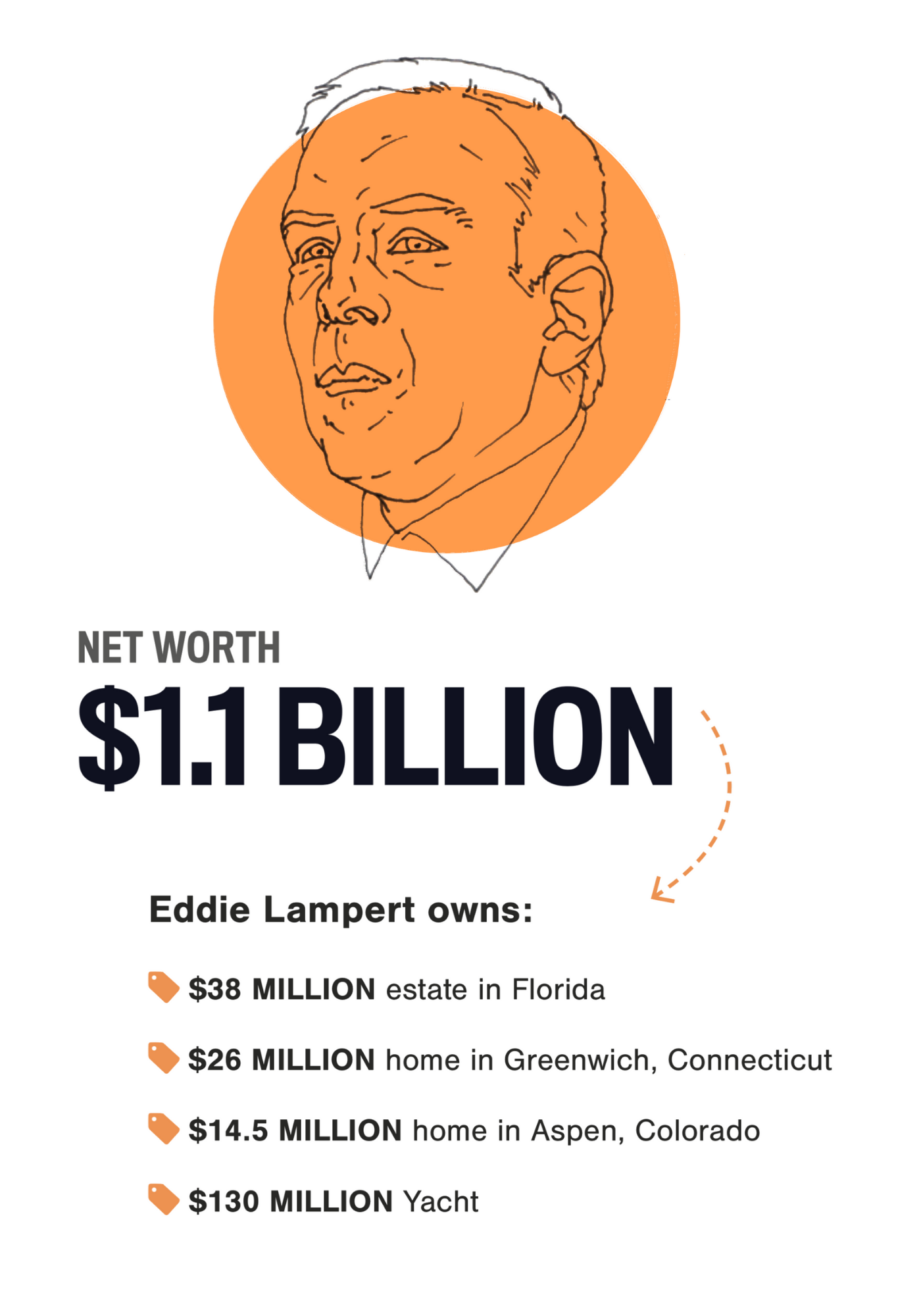

The Demise of Sears and Kmart

In 2003, Kmart was acquired by ESL Investments, a hedge fund founded by Eddie Lampert, who is also Chairman and CEO. Two years later, ESL Investments used a leveraged buyout to acquire Sears and then quickly merged the two companies. After he established Sears/Kmart, Lampert implemented dramatic cost-cutting steps, including shifting people from hourly pay to commission-based pay, cutting benefits, and forcing people to work unstable schedules with little advance notice for changing shifts. As Sears’ sales continued to decline, Lampert sold the Land’s End clothing and Craftsman tool brands, although they were among Sears’ most valuable assets. Lampert also created and chaired a real estate company, Seritage, which bought a set of Sears’ stores for $2.7 billion. Sears was then forced to pay rent on the stores it previously owned. ESL earned $400 million in interest and fees for lending money to the cash- strapped retailer.84 In the last five years alone, Sears lost $5.8 billion. In the last decade Sears closed over 1,000 stores and 260,000 employees lost their jobs. In October 2018, when Sears filed for bankruptcy protection, it had $11.3 billion in liabilities, $5.6 billion in debt, and only $7 billion in assets. ESL, on the other hand, made millions in interest and fees it charged on the company’s debt and profits from sales of assets and payments made to ESL’s other holdings like Seritage.

Jenny Miller is a single mother of three children living in Columbus, Wisconsin who worked at Payless for almost 22 years. In November 2018 Jenny was diagnosed with breast cancer. She worked hard through Thanksgiving, saving as much as she could in preparation to take a leave of absence to get treatment. In January 2019, shortly before she was scheduled to take her medical leave, Jenny’s position was terminated. While Payless told Jenny that she would receive a 12 week severance package, the payments stopped after two weeks of pay. She also lost her health insurance. Since then Jenny secured health insurance through the state and has relied on tax returns and donations from family and friends to cover monthly expenses.

PART IV

RIPPLE EFFECTS: THE IMPACT OF PRIVATE EQUITY ON LOCAL ECONOMIES, CITIES, AND STATES

Beyond the direct and indirect job losses, Wall Street’s dominance in retail has caused far-ranging economic impacts on states and local communities. Private equity and hedge fund-driven bankruptcies significantly reduce the sales and real estate tax revenue that states need to fund vital public programs. During retail bankruptcies, Wall Street firms renege on retirement and pension benefits for both current and former employees with devastating impacts on families. Public pension funds, which are major investors in private equity firms, have seen subpar returns on their investments compared to the S&P 500, which hurts the long-term financial security of an even broader swath of people.

IMPACT ON EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT

Private equity and hedge fund owners have not only laid off nearly 600,000 retail workers, but they have been quick to use the bankruptcy process to dump their obligations to current and future retirees who worked for the bankrupted companies. That means the retail bankruptcies and closures will have negative effects on workers, retirees, and communities for years to come.

Hedge fund ESL Investments, controlled by billionaire Eddie Lampert, had been the majority owner of Sears for more than a dozen years prior to the retailer’s October 2018 bankruptcy filing. ESL oversaw the dismantling of the 125-year-old retailer — the company has dropped more than 260,000 jobs during ESL’s tenure.

Earlier this year, a bankruptcy court approved the sale of hundreds of Sears stores, as well as the Sears brand and its intellectual property, to a new ESL-owned vehicle, Transform Holdco. But Sears’ pension obligations to 90,000 Sears employees were left in limbo. The U.S. government will end up taking over much of those obligations. The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), a federal government agency set up to protect pensioners, will assume responsibility for Sears employees’ pensions. The PBGC sued Sears in February 2019, alleging two Sears Holdings’ pension plans were underfunded by $1.4 billion. While the PBGC will insure all Sears employees are paid the pensions they are due, Sears liquidation means retirees will lose health insurance.

“ESL’s current bid to ‘save the company’ is nothing but the final fulfillment of a years-long scheme to deprive Sears and its creditors of assets and its employees of jobs while lining Lampert’s and ESL’s own pockets,” according to a January 2019 filing in Sears’ bankruptcy case by attorneys for Sears’ unsecured creditors (which include the PBGC). According to Lampert, if Sears could have taken billions in hard earned workers’ retirement and instead “employed those billions of dollars in its operations, we would have been in a better position to compete with other large retail companies, many of which don’t have large pension plans, and thus have not been required to allocate billions of dollars to these liabilities.”

SUN CAPITAL HAS LEFT BEHIND $280 MILLION IN DEBTS TO WORKERS’ SEVERANCE AND PENSIONS

Sears is by no means the only example of private equity firms dropping pension obligations during the bankruptcy process. Twenty-five of Sun Capital’s companies have filed for bankruptcy since 2008, which is one of every five companies it owns. Over the past 10 years, five of those bankrupt companies owned by Sun Capital left behind $280 million in debts to employee pensions. When Marsh Supermarkets filed for bankruptcy in 2017, its owner, Sun Capital, recovered its investment but left more than $80 million in debts to workers’ severance and pensions unpaid. As the Washington Post reported, “‘They did everyone dirty,’ said Kilby Baker, 70, a retired warehouse worker whose pension check was cut by about 25 percent after Marsh Supermarkets withdrew from the pension. ‘We all gave up wage increases so we could have a better pension. Then they just took it away from us.’”

FAILURES OF WALL STREET-OWNED RETAILERS ALSO HIT PENSION FUNDS’ INVESTMENT RETURNS

The collapse of private equity and hedge fund- owned retailers not only hit the retirement savings of their employees but also damages the economic security of millions of other employees and retirees who participate in pension funds that are invested with those private equity firms. Employee pension funds make up the largest group of investors in private equity and they depend on investment returns to pay benefits for millions of retirees. Retail bankruptcies often mean losses for pension investors.

For example when Toys “R” Us went bankrupt, the pension funds that were invested in the KKR and Bain Capital (which owned Toys “R” Us), reportedly lost several million dollars. While these losses were spread out across hundreds of investors and represented a small amount relative to those pension funds’ overall assets, the loss affected pension funds including the Washington State Investment Board, the Oregon Investment Council, the New York State Common Retirement Fund, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the Minnesota State Board of Investment, the Michigan Department of Treasury, and the State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio.

IMPACT ON STATE AND LOCAL TAX REVENUE

Failures at Wall Street-owned retailers also directly reduced the tax bases of states and localities. Most U.S. states and many municipalities and localities collect sales tax. When retailers shut their doors, those sales and sales tax revenues to states and municipalities disappear. For example, Toys ”R” Us’ 2016 net sales totaled $7.131 billion. Toys “R” Us’ 2018 closure resulted in clear reductions in sales tax revenue.

Beyond sales taxes, many municipalities rely heavily on local real estate taxes for revenue. Retail closures mean vacant stores, reducing the value of real estate and thus property tax receipts. And, that decline in value is not confined to shuttered retail stores themselves. Vacancies can lead to more vacancies, as customers may avoid malls that have lost an “anchor tenant” or have many empty storefronts. According to Bloomberg, the U.S. store closures announced in 2017 represented a record 105 million square feet of real estate. By April 2018, additional closures accounted for another 77 million square feet, according to data on retail chains compiled by the CoStar Group Inc.

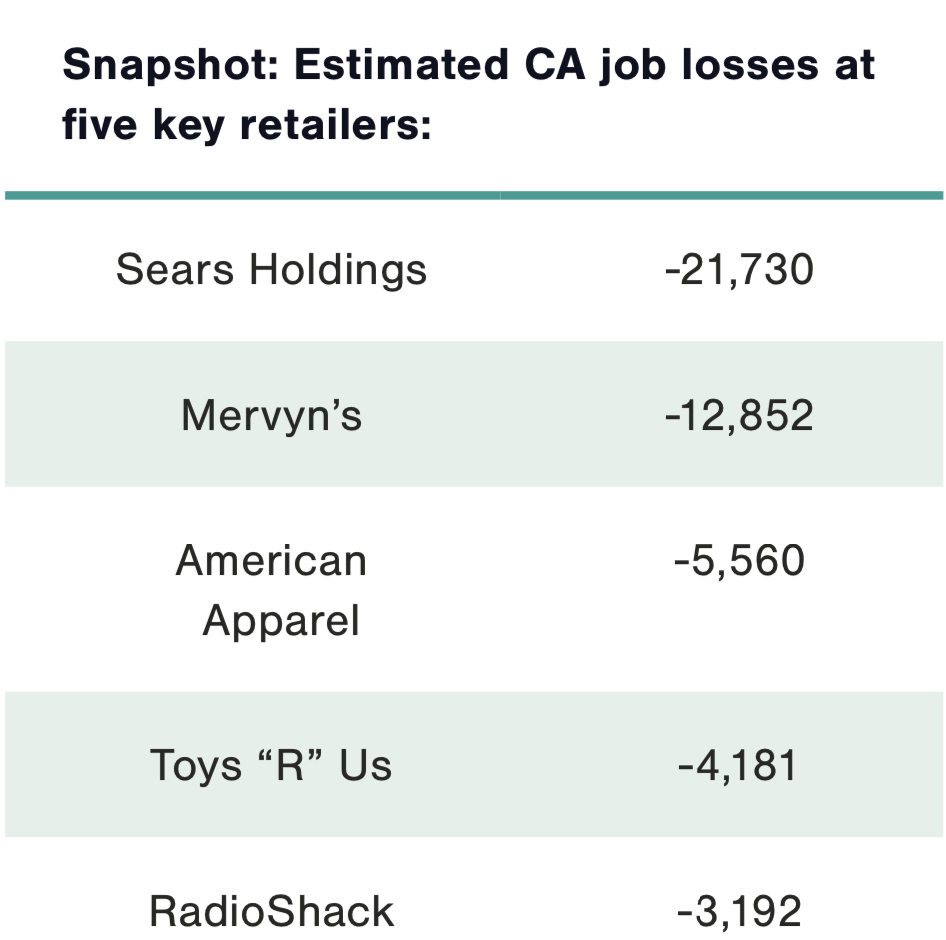

California State Profile

California has seen the greatest job losses from closures at private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers in recent years, losing at least 55,000jobs at five key retailers for the state.

Retailer Sears Holdings, owned by hedge fund ESL investments, has shed nearly 22,000 jobs in California since the 2005 takeover. The 2008 bankruptcy of department store chain Mervyn’s, owned by private equity firms Sun Capital, Cerberus Capital Management, and Lubert Adler Partners, cost nearly another 13,000 jobs.

Bloomberg Businessweek wrote of the private equity firms’ actions at Mervyn’s:

When Sun Capital, Cerberus Capital Management, and Lubert Adler Partners bought Mervyns from Target (TGT) for $1.2 billion in 2004, they promised to revive the limping West Coast retailer. Then they stripped it of real estate assets, nearly doubled its rent, and saddled it with $800 million in debt while sucking out more than $400 million in cash for themselves, according to the company. The moves left Mervyns so weak it couldn’t survive.

Mervyns’ collapse reveals dangerous flaws in the private equity playbook. It shows how investors with risky business plans, unrealistic financial assumptions, and competing agendas can deliver a death blow to companies that otherwise could have survived. And it offers a glimpse into the human suffering wrought by owners looking to turn a quick profit above all else.

More recently, California was home to the largest number of Toys “R” Us employees (more than 4,000), who lost their jobs in June 2018 after KKR, Bain Capital, and Vornado took the retailer into bankruptcy. Other private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers that have closed stores in California include Payless Shoesource, Sports Authority, Charlotte Russe, Wet Seal, Coldwater Creek, Hot Topic, Aeropostale, Pacific Sunwear of California, Guitar Center, Rue21, and Shopko.

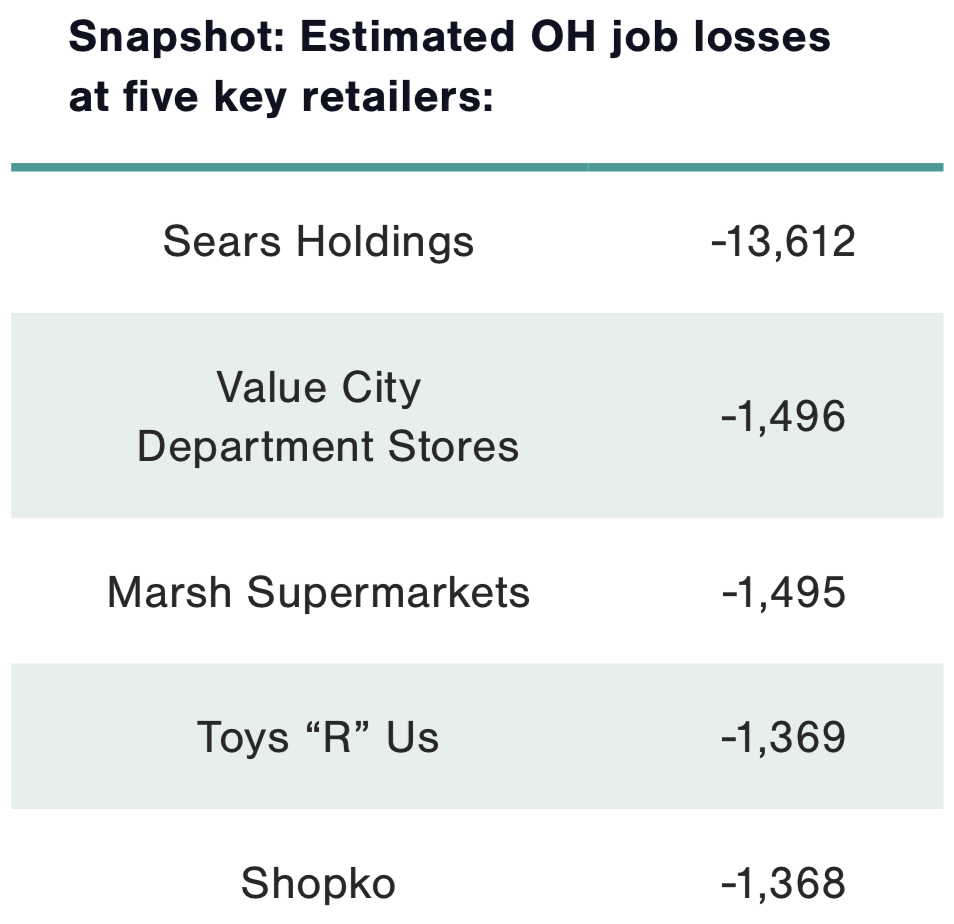

Ohio State Profile

While Ohio has been hit hard by the loss of manufacturing jobs, private equity firms and hedge funds have not made the situation any easier for the Midwestern state. Closures of stores by private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers have cost Ohio at least 22,000 jobs at five key retailers over the last several years.

While the decline of Sears under the ownership of hedge fund ESL Investments has had the greatest impact, leading to an estimated 13,600 job losses in the state, Ohio has also been hit by the closure of chains such as Toys “R” Us, Shopko, and Marsh Supermarkets.

Two retail chains owned by private equity firm Sun Capital — Marsh Supermarkets and Shopko — have each shed over 1,000 jobs in Ohio. Indiana-based Marsh Supermarkets, founded in 1931, began to struggle; its private equity owner, Sun Capital, began selling off valuable real estate assets. In May 2017, Marsh Supermarkets announced it would close its remaining 44 stores. While thousands lost their jobs, Sun Capital recovered its initial investment and left more than $80 million in debts to workers’ severance and pensions unpaid. The Washington Post reported:

“It was a long, slow decline,” said Amy Gerken, formerly an assistant office manager at one of the stores. Sun Capital Partners, the private- equity firm that owned Marsh, “didn’t really know how grocery stores work. We’d joke about them being on a yacht without even knowing what a UPC code is. But they didn’t treat employees right, and since the bankruptcy, everyone is out for their blood.”

In January 2019, Shopko, owned by Sun Capital and other private equity firms, filed for bankruptcy. The company recently announced that it will close all of its stores by summer 2019. Shopko’s closure will lead to an estimated 1,370 job losses in Ohio. Prior to Wisconsin- based Shopko’s bankruptcy, Sun Capital and other owners drew $170 million in dividend payments from the retailer.

Other private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers that have closed stores in Ohio include RadioShack, Payless Shoesource, Charlotte Russe, Wet Seal, Coldwater Creek, Aeropostale, Sports Authority, American Apparel, Hot Topic, and Pacific Sunwear of California.

ESL’S EDDIE LAMPERT SPENDS BIG WHILE SEARS PENSIONERS STRUGGLE

While Sears went bankrupt and passed on employees’ pension obligations to the government, Eddie Lampert lived and worked in luxury. With a current net worth of $1.1 billion, Lampert owns at least three lavish homes: a $38 million estate on an island in Florida known as “the billionaire bunker;” a $26 million 10,000 square foot house on six acres of waterfront land on the Long Island Sound in Greenwich, Connecticut; and a $14.5 million home in the wealthy ski resort town of Aspen, Colorado. He also owns a 288-foot yacht, worth $130 million, named The Fountainhead. Reportedly, Lampert ran Sears while working from his $38 million Florida island estate.

Lampert began making connections to powerful elites at Yale, where he became a member of the notorious, elite secret society Skull and Bones, whose powerful members include former president George W. Bush and billionaire private equity manager Stephen Schwarzman (who is CEO of the Blackstone Group). His roommate in college was Steve Mnuchin, who is now Trump’s Secretary of the Treasury. Mnuchin served on Sears’ board of directors from 2005 to 2016.

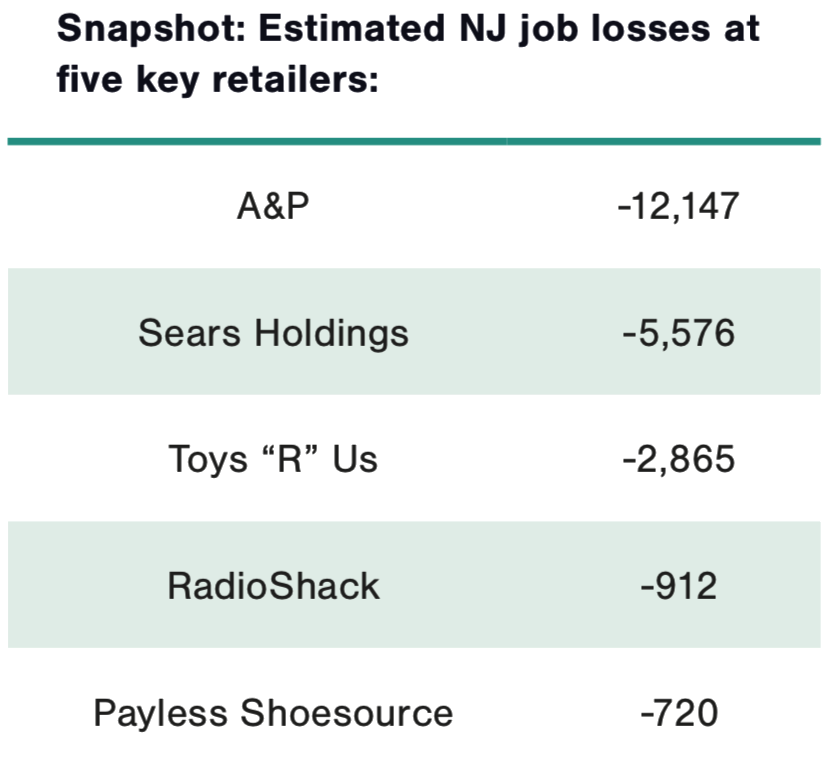

New Jersey State Profile

New Jersey has seen a number of private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers shutter in recent years, resulting in more than 25,000 lost jobs a five key retailers.

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. (A&P) — which operated grocery stores including A&P, Food Emporium, Pathmark, Superfresh, and Waldbaum’s—emerged from bankruptcy in 2011 after investments by private equity firms Yucaipa Cos, Mount Kellett Capital Management, and Goldman Sachs Asset Management.

Yet just a few years later, in 2015, the Montvale, New Jersey-based retailer filed for bankruptcy again. While some A&P stores were sold to other grocery chains, thousands of A&P employees in New Jersey lost their jobs.

When retailer Toys “R” Us shut its doors in June 2018, New Jersey lost thousands of jobs at the stores and its Wayne, New Jersey, corporate headquarters. In addition to being a major employer in the state, Toys “R” Us’ Wayne headquarters was the third-largest taxpayer in the township, paying $2.7 million in 2017. Following the bankruptcy announcement, rating agency Moody’s noted that the Toys “R” Us bankruptcy could negatively affect the township’s economy and its triple-A credit rating. The negative fiscal impact of Toys “R” Us’ bankruptcy was not limited to Wayne Township.

Other private equity and hedge fund-owned retailers that have closed stores in New Jersey include Sports Authority, Value City Department Stores, Aeropostale, Charlotte Russe, Wet Seal, Coldwater Creek, American Apparel, Pacific Sunwear of California, Hot Topic, and Rue21.

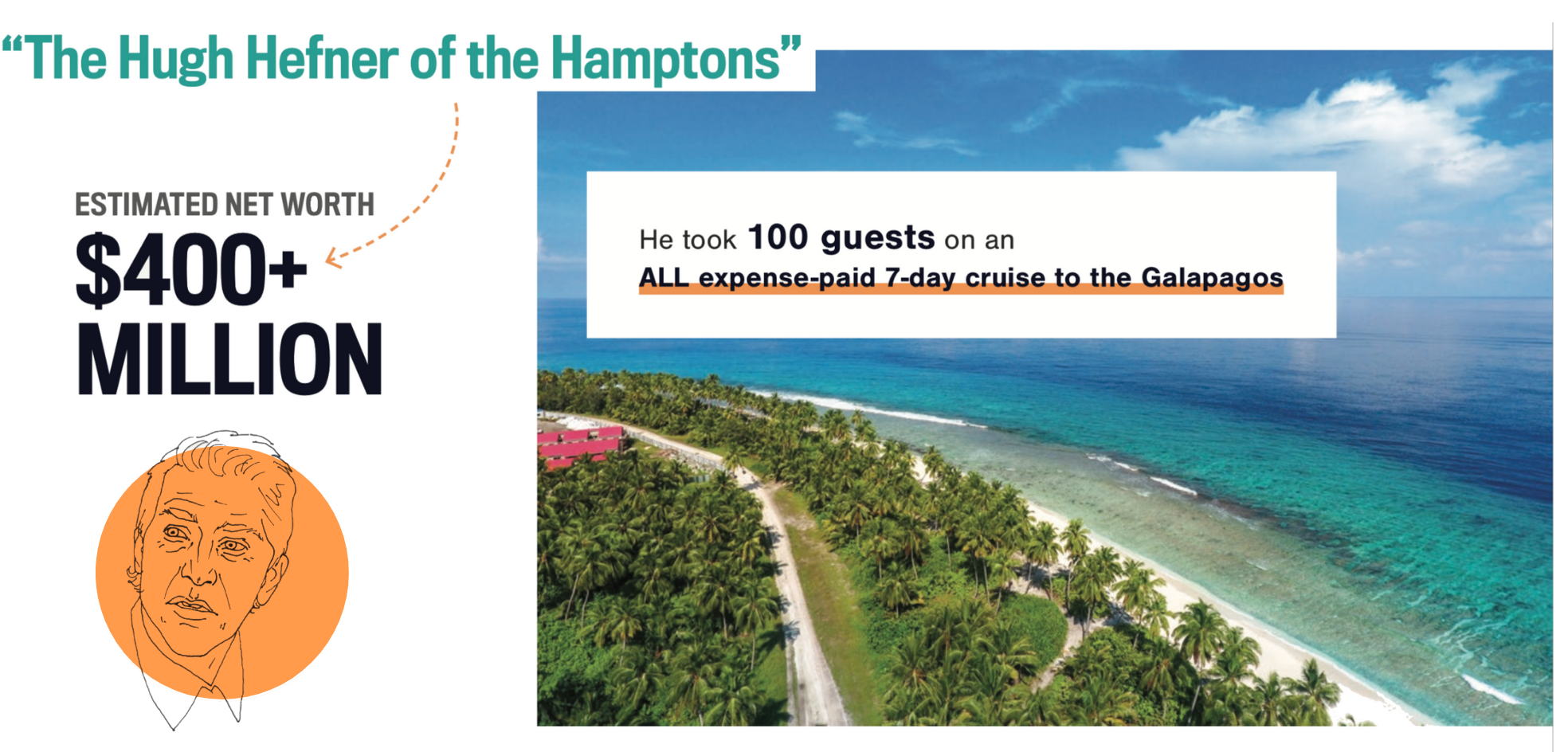

Sun Capital’s Party Boy Marc Leder

While Sun Capital has reneged on Marsh Supermarkets workers’ pension obligations and cut benefits, Sun Capital co-founder and co-CEO Marc Leder has become wealthier and earned a reputation for throwing raucous, extravagant parties.128 Leder made enough money to buy numerous multimillion-dollar properties, including a $22 million home in the Hamptons; two apartments in the NoHo neighborhood of Manhattan, reportedly paying $30 million for both of them; a $4.45 million house in a golf course community in Boca Raton, Florida; and a $15 million penthouse apartment in South Beach in Miami. He is also co-owner of the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers and the NHL’s New Jersey Devils.130 While his precise net worth is unknown, his former wife estimated it was over $400 million in a 2009 divorce filing.

He hosted the infamous 2012 Mitt Romney $50,000 per plate fundraiser at his Boca Raton house where Romney made his “takers” comments about supporters of President Barack Obama: “All right, there are 47 percent who are with him, who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it.”

Earning the nickname “the Hugh Hefner of the Hamptons,” Leder has hosted numerous unique and expensive parties over the years. For example, in 2015, he chartered a 290-foot cruise ship, taking 100 guests, who created the hashtag #ssleder for the event, on an all- expenses-paid 7-day cruise to the Galapagos Islands in Ecuador. His elaborate Hamptons blowout bashes became infamous. For example, in 2013, following numerous complaints from neighbors and noise violations from the town where his $900,000 summer rental was located, he struck a deal with the town to be permitted to host a July 4th party by donating $10,000 to the Southampton Youth Services and putting $50,000 in escrow in case of damages.

Madelyn Garcia is from Boynton Beach and worked at Toys “R” Us for 30 years, where she was a store manager until her store closed in June 2018. Madelyn lost her mother and her job in the same week. Madelyn has family in Puerto Rico who were impacted by the devastation of Hurricane Maria in 2017. She visited the island often with her mother and in recent years saw prices skyrocketing and her family facing financial struggles. Madelyn was shocked to learn that hedge funds involved in the liquidation of Toys “R” Us were also involved in the crushing debt crisis on the island. Wall Street greed was impacting her life in more ways than one, and, until then, it wasn’t an issue her coworkers or family were following closely.

Lone Star’s John Grayken Tax Exile

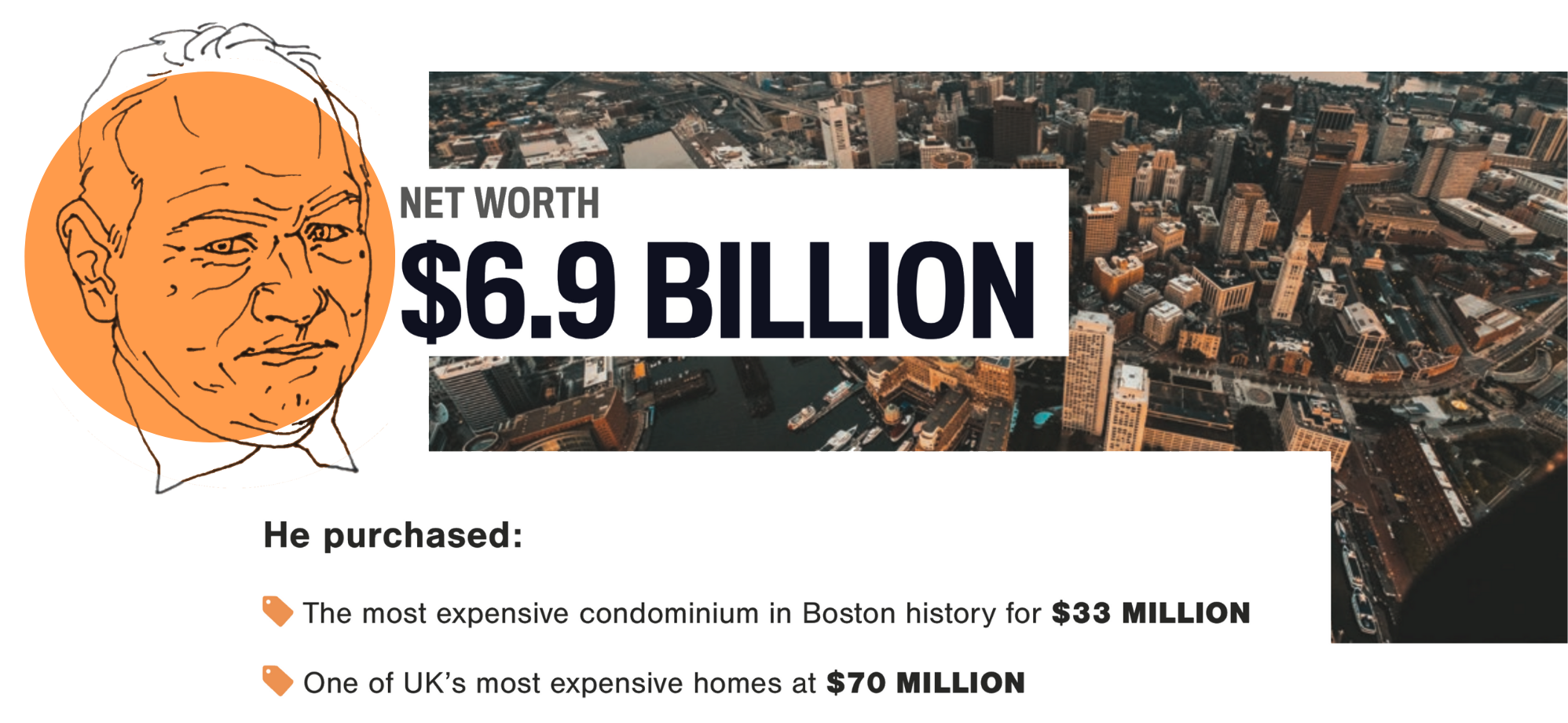

John Grayken founder and sole owner of Lone Star Funds, has a net worth of $6.9 billion, putting him second only to Blackstone Group chairman Stephen Schwarzman in net worth among private equity managers in the world. Despite this massive wealth, Grayken took extreme steps to avoid paying U.S. taxes. In 1999, he renounced his U.S. citizenship and became a citizen of Ireland. Nevertheless, Grayken continues to work and live part time in the United States, although he cannot spend more than 120 days in the United States annually without having to pay U.S. taxes. Dallas-based Lone Star is a U.S. company, and Grayken owns opulent domestic properties, including a 13,000 square foot, ten and a half bathroom Boston penthouse apartment. He bought the luxury apartment for $33 million in 2016, then the most expensive condominium sale in Boston history. He also owns one of the UK’s most expensive homes — $70 million, 17,500 square foot London mansion — as well as a 15-bedroom house on twenty acres outside London, which was previously featured in the movie The Omen, and a large house overlooking Lake Geneva in Switzerland. Meanwhile, Lone Star has made money buying distressed and delinquent home mortgages, a strategy that became particularly lucrative in the wake of the financial crisis. Its mortgage company, Caliber Home Loans, is “infamous for its tactics as a servicer of subprime loans.” One study found that Caliber was among those doing “the worst job of complying with the servicing rules” and had a high number of foreclosures. In 2015, the New York Attorney General opened an investigation into Lone Star’s “heavy-handed mortgage-servicing tactics, including aggressive foreclosures.”

PART V

HOW DID WE GET HERE? PRIVATE EQUITY FIRMS AND HEDGE FUNDS ARE UNACCOUNTABLE TO REGULATORS

Despite the enormous risks posed to workers, creditors, and the economy, private equity and hedge funds historically have been exempt from many key regulations governing mutual funds, investment banks, and commercial banks. While public companies are required to disclose detailed information about their income, expenses, and overall performance, private equity-owned companies are not. In addition, private equity funds have minimal disclosure requirements. Consequently, investors and the public often have limited or no meaningful transparency into private equity investments.

The limited existing disclosure requirements only highlight the urgent need for more accountability. The 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act added some reporting requirements for private equity and hedge funds with more than $150 million in assets. It also required the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to begin conducting examinations of private equity firms’ practices. In 2014, after its first round of examinations, Andrew Bowden, then Director of the SEC’s Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations, reported, “When we have examined how fees and expenses are handled by advisers to private equity funds, we have identified what we believe are violations of law or material weaknesses in controls over 50% of the time.” In the two years following, several major private equity firms paid hundreds of millions of dollars to settle SEC charges that they misled investors about the fees.

Unfortunately, Dodd-Frank did not institute regulation of leveraged buyouts or other key aspects of private equity’s business ventures. The existing regulations fail to require the SEC to monitor many of the private equity industry’s core business activities.

WALL STREET FIRMS USE TAX LOOPHOLES AND THE BANKRUPTCY CODE TO THEIR ADVANTAGE

Private equity firms use a host of strategies in their business dealings to boost profits and avoid paying their fair share.

Tax Loopholes

Exploiting tax loopholes is central to private equity’s business model. Despite being some of the wealthiest people in the country — many earning hundreds of millions of dollars a year — private equity managers pay taxes at a lower rate than teachers, firefighters, and nurses. While a few, like John Grayken of Lone Star Funds, have gone so far as to renounce their U.S. citizenship to avoid paying taxes, most private equity managers use some of the following tax loopholes to avoid paying their fair share:

- Carried Interest Loophole – Private equity managers structure their giant pay packages as investments, in order to have their compensation taxed at a far lower rate than ordinary income. They are often taxed at the 20% long-term capital gains tax rate, instead of being taxed in the 37% income tax bracket. Despite not actually putting their own capital at risk, private equity managers are able to pay taxes at this lower capital gains rate.

- Misclassification of Monitoring Fees – Private equity firms often push an acquired company to sign a management agreement, obligating it to pay “monitoring fees” to the private equity firm for periods of ten years or longer. The fees, which can exceed hundreds of millions of dollars, are supposedly paid in exchange for vaguely described monitoring, financial, and consulting services. If the management agreement is terminated, the private equity firm is often entitled to receive the full value of the contract even though its obligation to perform any services ceases. Portfolio companies typically deduct these fees as ordinary business expenses, a move that reduces their taxes.

- Deducting Interest Payments – Until quite recently, tax law enabled private equity firms to deduct the interest on leveraged buyouts from pre-tax income. On the other hand, dividend payments in equity financing were not tax deductible and therefore less attractive. That meant the tax code incentivized large amounts of debt. The 2017 tax bill put caps on how much interest can be deducted, which should reduce but not eliminate incentives to impose excessive leverage on acquired companies. Significant interest deductions are still permitted, and in addition real estate companies are exempt from the deduction cap. In practice, private equity firms that split companies into operating and real estate firms may be able to transfer all the debt to the real estate side of the business and continue reaping benefits of the tax loophole.

Overall, Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 was a significant boon to private equity. It reduced the corporate income tax rate to 21% (a significant drop in taxes for many private equity-owned companies) while preserving the carried interest loophole, in most circumstances, and publicly-traded partnerships loophole. Changes in the interest deductions are unlikely to fundamentally change the structure of private equity deals. Private equity firms utilize debt not just because of the tax benefit it provides, but also because it magnifies returns (assuming the portfolio company’s returns are positive) and allows them to spread capital across a greater number of companies.

MANIPULATION OF THE BANKRUPTCY CODE

Private equity firms are masters at manipulating the bankruptcy code to ensure that they are rewarded over workers, pension funds, and other creditors even if a firm does go into bankruptcy. Since the private equity firm can control the firm’s debt structure and management before the bankruptcy and has access to highly paid lawyers during the procedure, they can manipulate the process to their own advantage. Pension funds are frequently among the largest unsecured creditors of businesses in bankruptcy. According to Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation data, “at least 51 companies have abandoned pension plans in bankruptcy at the behest of private equity firms” from 2001 to 2014, dumping $1.6 billion in obligations onto the PBGC and costing over 100,000 affected workers and retirees at least $128 million.

A PATH FORWARD

Wall Street’s expansion into retail has threatened the stability of our economy, compounded income and wealth inequality, and gambled with the livelihoods of millions of working people. As private equity and hedge fund managers preserve and exploit lax regulations and lucrative tax loopholes to the detriment of working families, there are growing calls for reform from policymakers, local communities, and impacted workers.

Reform will not be simple because private equity funds use many methods to extract value from acquired firms and their workers. An effective approach must address all the key elements of the private equity business model.

- The first is the private equity firm’s lack of accountability for decisions it makes that affect their portfolio firms. A prime example is the leveraged buyout, which private equity firms use to impose the costs of acquisition and financial risks on the firm being acquired and indirectly on its workers and their community, while avoiding any liability for LBO debt. Policymakers need to fundamentally re- examine the lack of accountability for debt in the leveraged buyout model and, more broadly, the lack of accountability of private equity general partners for decisions made at the firms they control.

- Another related area of reform includes bankruptcy laws, which must give greater priority to the interests of working people. Empowering workers in the bankruptcy process can prevent legal gamesmanship. Bankruptcy law currently allows too much leeway for private equity general partners to hold onto cash they drained from portfolio companies that could have helped keep the company afloat. In practice, this limits the funds available to support workers and communities impacted by the bankruptcy. This can have devastating results for people faced with sudden unemployment.

- Finally, the regulatory oversight of private funds needs to be improved, especially regarding disclosure of information and duties of fair play to outside investors in these funds.

Wall Street’s expansion into retail and risky deals have led to more than a half a million retail job losses in the last decade. The stakes are high for the one million additional people working in retail who could lose their jobs and livelihoods in the coming years. This report has highlighted the urgent need to regulate private equity firms and hedge funds in order to curb the high-risk financial practices that extract wealth, destabilize employers, and negatively impact working people.

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Jim Baker (Private Equity Stakeholder Project), Maggie Corser (Center for Popular Democracy), and Eli Vitulli (Center for Popular Democracy). It was edited by Vasudha Desikan and Lily Wang (United for Respect); Marcus Stanley, Heather Slavkin, and Patrick Woodall (Americans for Financial Reform); Michael Kink (Hedge Clippers); and Emily Gordon and Connie Razza (Center for Popular Democracy).